The musical genre of nocturne

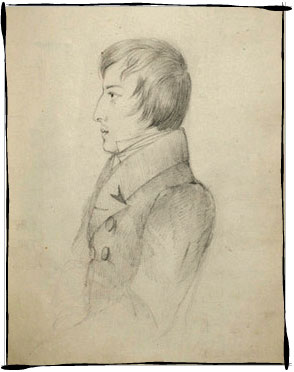

The nocturne is a musical composition that evokes the night-time mood; it is usually calm and meditative, although not devoid of contrasts. The Italian term notturno often appeared in titles of musical works in the 18th century, yet the French equivalent of the term was first used to describe a couple of lyrical compositions written for piano by John Field between 1812 and 1836. Field’s nocturnes also provided inspiration for Chopin, being idiomatic in nature and making a good use of the sound capabilities of new pianos; the sustaining pedal in particular enabled Field to widen the ambitus of harmonic accompaniment as compared to the existing and commonly used patterns of Alberti bass, necessarily suited to the hand span of the pianist. In the melodies of his nocturnes, Field introduced to piano music the cantabile of the Italian opera that he got to know during his stay in Russia in the first decade of the 19th century. As Liszt remarked in the introduction to the 1859 edition of Field’s nocturnes, they opened the way for all the similar compositions that had so far been published under the array of various titles such as songs without words, impromptus, or ballades, and it is in those compositions that sources of the works written to express one’s deepest, intimate feelings and emotions should be sought.

Although the emotional span in the majority of Field’s nocturnes is not very wide, and the phrase structure is often predictable, the aspect that made a great impression on the Romantic era composers including Chopin (who was a particular admirer of Field’s pianistic and composing skills) was a certain restrained elegance of the musical language and inventive figurations. At that time, nocturnes were written by pianists-composers such as Johann Baptist Cramer, Friedrich Kalkbrenner, Carl Czerny, Henri Bertini, Robert Schumann (Nachtstücke op. 23), Franz Liszt (transcriptions of his songs Liebesträume were described as nocturnes), Sigismund Thalberg or Theodor Döhler. Still, it is Chopin’s twenty Nocturnes (plus the posthumously published Lento con gran espressione in C sharp minor, described by Ludwika Chopin in the list of unpublished works as ‘Lento, of a nocturne character’) that occupy a special place in the history of the genre.

Chopin’s Nocturnes (particularly opus 48 no. 1) stand out for their emotional intensity - by far exceeding Field’s - and much richer melodic inventiveness. Sophisticated harmonies find their realization in complex, intricate counterpoint that never seems redundant or unnatural. The form often departs from the ABA pattern that constitutes the formal grounds for Field’s nocturnes.

Although Chopin’s times mark the peak of popularity of the nocturne, the genre never actually fell out of favour among later generations of composers. Gabriel Fauré wrote thirteen nocturnes; Vincent d’Indy, Eric Satie and Francis Poulenc also contributed to the development of the genre. Among late works of Franz Liszt we find the nocturne En rêve (1885); famous nocturnes were also written by Mikhail Glinka, Mily Balakirev and Pyotr Tchaikovsky (Op. 10 no. 1 in F major and Op. 19 no. 4 in C sharp minor), Edvard Grieg (Nocturne in C major Op. 54 no. 4), Rimsky-Korsakov (Nocturne in D minor), or Alexander Scriabin (Prelude and Nocturne for the left hand Op. 9). Nocturnes were also composed for the orchestra, a well-known example being A Midsummer Night’s Dream overture by Felix Mendelssohn, in which the nocturnal mood is created by the muted tone of the horn, just like in the 18th century notturno. George Bizet wrote an unpublished nocturne for orchestra, and the Trois nocturnes by Claude Debussy (Nuages, Fêtes and Sirènes) belong to the greatest achievements of the French impressionism in music.

Nocturne in D flat major Op. 27 no. 2

The pair of Nocturnes, Op. 27, attuned by two enharmonic aspects of a single key (C sharp minor / D flat major), seems an ideal realisation of two varieties of the genre.

The Nocturne in C sharp minor, the first of the pair, was composed as a nocturne of the elegiac variety. The Nocturne in D flat major, the second of the pair, is a complete opposite, with the idiom of the ‘romance’ variety of nocturne most pronounced. In the opinion of Chopin’s monographers, the composer produced nothing more perfect of the sort. Hugo Leichtentritt calls the cantilena that opens the work ‘achingly beautiful’. This opening theme, which is also the work’s principal theme, uttered dolce – always in a lonely (solo) voice – has its complement, pronounced espressivo, always in thirds and sixths that sound passionately (appassionato) and mellifluously. Yet it is the opening theme that reigns here, undergoing a succession of modifications. The last of them is quite breath-taking. The form of that Nocturne could be termed the anchor-variation one – we can feel in it the natural, eternal rhythm of return and reinvention striving towards the climax and the final calm.

André Gide, who left us a remarkably well-observed collection of thoughts entitled Notes on Chopin, captured this kind of music in words with exceptional intuition. On one of the pages of his notebook, he remarked: ‘[Chopin] seemed to be constantly seeking, inventing, discovering his thought little by little’. The writer warns us: ‘This kind of charming hesitation, of surprise and delight, ceases to be possible if the work is presented to us, no longer in a state of successive formation, but as an already perfect (…) and objective whole.’

Author: Mieczysław Tomaszewski (based on “Chopin. Człowiek, Dzieło, Rezonans” [‘Chopin. Man, Work, Resonance’])

Principles adopted for the main text

of the Nocturne in D flat major Op. 27 no. 2

We have adopted FE, being the latest authentic source in the process of publication of the Nocturne, as the basic source. We rely on A for the correction of errors and inaccuracies made by engravers. We include dynamic changes, variants and other annotations coming from the four extant teaching copies, as well as those noted down by Franchomme in FEFr.