The Ballade Genre

In the times of Chopin, the ballade had three equally popular connotations. The term “ballade” mainly referred to the literary form – combining characteristics of epic (narrative, plot), poetry (emotionality) and drama (dialogues and action), on themes drawn from stories and folk tales, plenty of fantastic events, magic and frequent interventions of supernatural powers. The genre, universalised by such authors as Gottfried August Bürger (Lenore), Johann Wolfgang Goethe (The Erlking), Friedrich Schiller (The Glove), Heinrich Heine (Lorelei) or Adam Mickiewicz (Świteź, Świtezianka), enjoyed great popularity in the era of Romanticism.

A natural consequence of the literary ballade’s popularity was to transfer it to the musical ground. Therefore, on the one hand, one created vocal ballades for solo voice or accompanied by an instrument, being a musical illustration of works by contemporary poets. The literary creation proved to be a remarkably graceful object to be set into music – fast-paced action, dialogues between the characters, supernatural phenomena, nature coming alive and eventually magic, fantastical personages – all these elements allowed to apply a number of unobvious musical resources and solutions: Harmonic, rhythmic, dynamic or agogic, which created an atmosphere corresponding to the ballade’s content and illustrated the events which were happening therein and the accompanying them emotions. Franz Schubert is an example of a composer who used the potential of literary ballades to the fullest; he composed music to, among others, collections of poetry by Schiller (e.g., Der Taucher), Goethe (e.g., Erlkonig) or Heine (songs from the cycle Schwanengesang). On the other hand, ballades started to appear in operas, as an element describing events taking place beyond the stage, often becoming an opportunity for composers to show their skills, hence also for a vocalist’s abilities. One of the most popular pieces of this kind was, among others, Raimbaut’s ballade from Giacomo Meyerbeer’s opera Robert the Devil (1831), as well as Senta’s ballade from Richard Wagner’s opera The Flying Dutchman.

The ballade as a strictly instrumental genre was not born until under Chopin’s fingers. The first sketches of the Ballade in G minor, Op. 23 were created already in the middle of the 1830s, three subsequent appeared in print in 1840-1843. The time during which Chopin worked on the ballades belonged to the most creative in his compositional career, as it was in 1835-1843 that such masterpieces as the Fantasy in F minor or four Scherzos were created, which, to a certain extent, are related to the ballades due to, among others, their free, yet at the same time extensive form. The form of the ballades is not based on schemes but on basic formal rules such as synthesis, antithesis, sequence, development, transformation, variation or reprise. The main driving force of the ballades is the theme and its transformations, while the means used to achieve this aim are mainly melodic, dynamic, agogic or rhythmic contrasts.

According to Robert Schumann’s memories, Chopin “would then say that he was incited to his ballades by a few poems by Mickiewicz.” Despite numerous attempts to find direct references to Świtezianka or Lorelei in Chopin’s ballades, the researchers have not been able to prove the existence of such a dependence. However, lack of a clear programme or illustrative character does not mean that it is pointless to look for a story in Chopin’s ballades. The content, unexpressed with words, is hidden in plenty of expression themes, while the narrative tone guides the hearer through the meanders of waving melodies or impulsive passages. Numerous contrasts introduce plot twists, while the unobvious harmonic solutions leave an impression of an understatement, obliging the hearer to interpret the open ending on his own.

Although it could seem that four pieces are not yet a genre, Chopin achieved a new quality in the ballades, different from the one in the genres he had written before. In spite of the clear genre affiliation, each of the ballades has its own unique character of an enormous emotional load. The gloomy Ballade in G minor, Op. 23 develops the form of sonata allegro in a particular way; in the Ballade in F major, Op. 38, the main driving force are contrasts; the Ballade in A-flat major enchants the hearer with its radiantly idyllic themes, while in the Ballade in F minor the lyrical element unfolds variationally, falling into a net of dense polyphony. This diversity of moods, even within one piece, narrative character and extensive form induced the researchers to determine the instrumental ballade as a “piano poem.”

It is hard to say whether the further fate of piano ballade is a consequence of Chopin’s pieces or whether it developed independently on the ground of vocal ballade. Although the works of this genre composed later by Johannes Brahms, Franz Liszt, Edward Grieg or Gabriel Fauré did not reach the level of Chopin’s ballades, they enjoyed a great popularity among the contemporary audience. The ballades by César Franck (Op. 9) and Liszt (the Ballade in D-flat major), similarly as Chopin’s ballades, did not refer to any literary original. However, a ballad from Op. 10 by Brahms already indicates a direct association with the Scottish ballade Edward from Johann Gottfried Herder’s collection The Voices of the People. The piano ballade also influenced the development of orchestral music, anticipating the creation of the symphonic poem genre.

Ballade in G minor, Op. 23

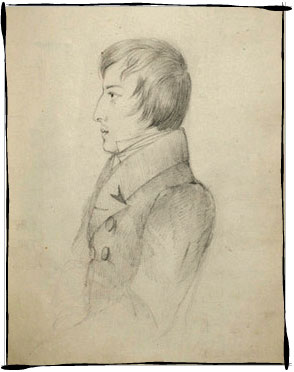

In 1836, a year after his first scherzo, Chopin published his first ballade. He dedicated it to one of his friends at the time, Baron Nathaniel Stockhausen, ambassador of the Kingdom of Hanover. Both the Baron and his wife took piano lessons from Chopin.

‘I have received from Chopin a Ballade’, Robert Schumann informed his friend Heinrich Dorn in the autumn of 1836. ‘It seems to me to be the work closest to his genius (though not the most brilliant). I told him [Schumann was writing the day after a meeting with Chopin] that of everything he has created thus far it appeals to my heart the most. After a lengthy silence, Chopin replied with emphasis: “I am glad, because I too like it the best, it is my dearest work”.’

Once again we are faced with a number of enigmas. Firstly, which of the ballades were Schumann and Chopin discussing? The first, in G minor, dedicated to Stockhausen? The second, in F major, had already been written at that time, and Chopin would dedicate it soon afterwards to Schumann. The edition, ‘à Monsieur Robert Schumann’, did not appear until 1840, as the work only acquired its ultimate form in 1839, in Majorca. In 1836, in Leipzig, Schumann heard its earlier version, which was different. And so everything suggests that the ballade closest to both Chopin and Schumann was the G minor. Also in Leipzig at that time, Chopin apparently confessed to Schumann that he was inspired to write his ballades by the ballads of Adam Mickiewicz. Schumann wrote expressly about this in his review of the F major Ballade.

And more questions arise. When did the moment of that initial inspiration from Mickiewicz’s poetry arise? And how deeply or extensively should that inspiration be understood?

Well, the Ballade in G minor shared the fate of the Scherzo in B minor: its provenance is not accurately documented. All we know is that it had been written by 1833 and was published three years later. A tradition confirmed by monographers links this work with Chopin’s sojourn in Vienna. The supposition is that it was sketched in the Austrian capital and possibly completed in Paris. Above all, however, the atmosphere, character and style of the G minor Ballade place it unquestionably closer to the B minor Scherzo and the first nocturnes and etudes than to the Rondo in E flat major, Variations in B flat major and Grand Duo Concertant. The Ballade has nothing in common with the ‘brilliant’ style to which Chopin returned during his early Paris years. It manifests pure romanticism, the first explosion of which in Chopin came during the two Warsaw-Vienna years between the autumn of 1829 and the autumn of 1831. That may be called Chopin’s period of Sturm und Drang.

It was during those two years that what was original, individual and distinctive in Chopin spoke through his music with great urgency and violence, expressing the composer’s inner world spontaneously and without constraint – a world of real experiences and traumas, sentimental memories and dreams, romantic notions and fancies. Life did not spare him such experiences and traumas in those years, be it in the sphere of patriotic or of intimate feelings.

As we are well aware, the appearance of the ballad in Central European culture has often been linked with the pre-Romantic movement of Sturm und Drang. More precisely, with the figures of Herder, as the theorist of that movement, Gottfried August Bürger, the author of the first ballad of the new sort, the famous ‘Lenore’, and then Schiller and Goethe, authors of ballads and romances, with Goethe’s ‘Erlkönig’ to the fore. That was the path taken by Adam Mickiewicz, who published a volume of ballads and romances in 1822.

For everyone, the ballad was an epic work, in which what had been rejected in Classical high poetry now came to the fore: a world of extraordinary, inexplicable, mysterious, fantastical and irrational events inspired by the popular imagination. In Romantic poetry, the ballad became a ‘programmatic’ genre. It was here that the real met the surreal. Mickiewicz gave his own definition: ‘The ballad is a tale spun from the incidents of everyday (that is, real) life or from chivalrous stories, animated by the strangeness of the Romantic world, sung in a melancholy tone, in a serious style, simple and natural in its expressions’. And there is no doubt that in creating the first of his piano ballades, Chopin allowed himself to be inspired by just such a vision of this highly Romantic genre. What he produced was an epic work telling of something that once occurred, ‘animated by strangeness’, suffused with a ‘melancholy tone’, couched in a serious style, expressed in a natural way, and so closer to an instrumental song than to an elaborate aria.

From the very first notes of this Ballade, we are engulfed in a balladic aura. We sense that this music means to tell us something extraordinary and strange. The dissonant note e flat that closes the opening recitative does not augur a happy end. (Interestingly, in the German edition it was altered to the consonant note d.) At the same time, we sense that it will be a tale of domestic, rather than foreign, occurrences. The rubato of the opening bars is like an awakening from meditation, the extraction of something from one’s memory.

And the tale commences. Spun out in an exquisitely beautiful melody, melancholically nostalgic, rising and falling in a regularly undulating 6/4 metre (an inseparable component of the balladic tone), the tale slowly grows. A new theme (or rather motif) enters, and the situation takes on dramatic accents, as if what has passed has suddenly become present. And there ensues what must inevitably ensue in a musical balladic tale: a special theme appears (in E flat major), from this world or perhaps another world. Subtle at first… dreamlike, one might say.

This theme also has its development, its shadow, its inseparable complement. What happens later unfolds like a sonata allegro. The exposition is followed by a development section, in which the two themes, transferred to another tonal sphere (A minor and A major), undergo wholesale transformation and an episode with a new theme comes to the fore. Then comes a reprise, presenting the two themes in their proper keys, though in reverse order. And the whole thing is crowned with a dynamic, sparkling coda.

Yet speaking of the G minor Ballade in this way, we are entirely overlooking its balladic essence. After all, in this work a tale is being told. And its plot is subject to the laws of epic drama, not the rules of static form. We are drawn into a story that manifests itself before our eyes, only to withdraw a moment later into the distant world of past events. We are witness to extraordinary events that grow into tragic situations, witness to transformations (even metamorphoses): for example, when that subtle theme appears in a form that radiates power and might or when the main theme attains moments of ecstasy – appassionato.

One can hardly wonder that those interpreters with a soft spot for ‘programmatic’ thinking have been sorely tested by the mysteriousness of this balladic tale. Keys have been sought and tried out. Indeed, that has been done in relation to all four ballades. Yet all in vain, or at least without any sensible effect. None of Mickiewicz’s ballads have been successfully conjugated – barring suspicious procedures – with Chopin’s ballades. Attempts have been made to consider the G minor Ballade as an equivalent of the romantic-heroic tale told by Mickiewicz in Konrad Wallenrod. But those attempts must also be regarded as senseless and fruitless. The language of Chopin’s music is the language of algebra, so to speak, and not of arithmetic. It does not need any concrete values to be set beneath it. It inhabits the realm of feelings and moods, experiences and passions that are unalloyed, not embroiled in detail and anecdote.

Author: Mieczysław Tomaszewski

A series of programmes entitled ‘Fryderyk Chopin's Complete Works’

Polish Radio 2