The musical genre of Tarantella

Dance genres occupy an extraordinarily important place in the Chopin oeuvre. In addition to national Polish dances like the polonaise, mazurka or krakowiak, Chopin also reached for genres originating in other countries as he composed dance miniatures directly inspired by contemporary trends, popular across European ballrooms, or his personal experiences of travelling Europe. Besides the ecossaises, classic minuet or splendid bolero written in his youth, Chopin also turned to the Italian tarantella.

The tarantella is a folk dance of the Italian South, also welcomed by artistic musical Europe. The name of the dance derives from the town of Taranto in Apulia. The tarantella found a legitimate place among court dances, where it was usually performed by a couple inside a ring of other watching dancers, who accompanied the dancing couple with the sound of castanets and tambourines and who also sometimes supported the dancers by singing - these were simple-structure melodies, of a changing mode in lively accelerating 3/8 or 6/8 time.

A commonly relayed story has it that the tarantella’s origin is connected with a frenzied dance - a cure for bites of the tarantula wolf spider, whose name also derives form the same time of Taranto. Tarantism was a common disease in Southern Italy between the 15th and 17th centuries, however, it was more a hysteria type rather than a consequence of a spider’s bite. Athanasius Kircher in his work Magnet of 1641 described eight melodies used to cure tarantism. Those melodies are characterised by regular phrasing and - contrary to the folk tarantella - double time. Melodic figures are comprised of frequent repetitions of sounds of the same pitch, scales runs and arpeggios.

The tarantella gained popularity as a concert piece in the 19th and 20th centuries. Tarantellas in 6/8 time with a tempo marking of Presto, Prestissimo or Vivace were often virtuoso pieces. The characteristics of tarantella as a folk dance are reflected in its piano form - the phrasing being rather regular, with melodics of a dance, however, diatonic scales are often replaced by virtuoso chromatic scales. The division of its form into sections is emphasised by modulation and contrasting tempos. Among the concert tarantellas it is worth mentioning those written by Chopin (Op. 43) and List (Venezia e Napoli, 1859, nr. 3). Slightly less virtuoso pieces are tarantellas composed by L. M. Gottschalk (Op. 67), Stephen Heller (Op. 85), Anton Rubinstein (Op. 82), Rachmaninov (Op. 17), or Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (Op. 156).

Tarantella-like passages would also appear as final parts in genres such as the sonata, symphony or suite. Carl Maria von Weber used tarantella’s motor rhythm in his Piano Sonata, Op. 70; Chopin’s finale of Sonata in G minor, Op. 65 for piano and cello also has the tempo and lively rhythm of tarantella. Richard Strauss also introduced a few Italian themes, including tarantella, to his Aus Italien, Op. 16. Mendelssohn described the final part of his Italian Symphony, Op. 90 as Saltarello, even though the character of the main theme in legato is close to tarantella. The concert tarantella was many times parodied - the best example is Rossini’s Tarantelle pur sang, where the wild tarantella is interrupted twice by a religious procession accompanied by the sound of bells.

Tarantella in A flat major, Op. 43

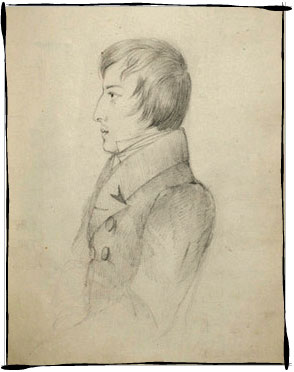

‘I hope I’ll not write anything worse in a hurry’ – such was Chopin’s rather unflattering assessment of the Tarantella.

Whilst that opinion would appear to be expressive of coquetry or nonchalance, it might also contain a dose of deliberate self-criticism, as the Tarantella represents ‘a work from a period of transition’. Close in ‘spirit’, tone and character to both the Bolero and several Waltzes (Opp. 18, 34 and 42), it is embroiled in a period of scherzos, ballades, nocturnes and sonatas. That does not mean that it may be called an unsuccessful work. It is rather a curious piece, and one that is unexpected in this particular period in the Chopin oeuvre.

There is no way of ascertaining why Chopin decided to write this work – what inspired him to do so. One might consider some fleeting contact with popular Italian music during the spring of 1839, in Genoa, but we have no details of that episode in his expedition (with George Sand and her children) to the south of Europe. It might also have been a commission from a publisher, though there are no documents to that effect. Then there is a third possible explanation: his fascination with Rossini and with his vocal tarantella, which (under the title ‘La Danza’) became a hit of its day. And this last hypothesis would appear to be closest to the truth. We know that Chopin was familiar with Rossini’s Tarantella, and so we might be dealing with a transferral of this dance-vocal genre to the domain of purely instrumental music – for piano. Shortly after arriving in Nohant, Chopin wrote to Julian Fontana with the manuscript of the Tarantella (to be copied): ‘Take a look at the Recueil of Rossini songs […] where the Tarantella (en la) appears. I don’t know if it was written in 6/8 or 2/8. Both versions are in use, but I’d prefer it to be like the Rossini’. It was in 6/8, and Chopin notated his Tarantella in that metre. In copying the manuscript, Fontana did not have to change a thing.

Chopin wrote the whole piece in a single breath, and essentially in a single rhythm; if it was altered, it was only through diminution.

Chopin, after Rossini, bids the pianist fall into a trance and stay there right to the end, without a moment’s pause. The dance is a mosaic of themes presented in the most regular eight-bar units. The themes are four in number and are divided by bridge passages. They are repeated and intertwined without a moment’s respite. The first theme sets the tone and character of a dance senza fine – one that, if repeated, could last endlessly. The bridge, or rather interlude, brings fleeting sharp accents, leaping out of the monotony of the dance motion. The second theme has the character of an episode, which slightly alters the narrative. It is followed by another interlude, also sharp and lively. The third theme brings some tunefulness. Finally, the fourth theme is distinguished by the strength of its accents and sforzatos. This real mosaic of themes – not contrasted, but merely differentiated, proceeding in a single tempo, to the point of breathlessness – is crowned by a frenzied coda.

‘[The Tarantella] is as little Italian as the Bolero is Spanish’, noted James Huneker with irony. ‘Chopin’s visit to Italy was of too short a duration to affect him, at least in the style of dance. It is without the necessary ophidian tang’. Ferdynand Hoesick went even further in his criticism: ‘The Tarantella was written by an incomparable master, but he wrote it soberly and with difficulty. In this ostensible ardour, there is coldness. Only Arthur Hedley defended it, although still not entirely: ‘it catches the spirit of the frenzied dance’, but ‘there is no Italian gaiety’.

Author: Mieczysław Tomaszewski

Principles adopted for the main text of

Tarantella A-flat major, Op. 43

We have adopted FE as a source which:

- comprises the work’s text written in full without any abbreviations according to Chopin’s request as expressed in his letter to Fontana;

- includes corrections made most probably by Chopin to one of the lost Fontana’s copies - [FC2]

- was most probably perfunctorily corrected by Chopin

To eliminate errors and inaccuracies we compare it with A and FC3. We include annotations in the teaching copy and correct rather numerous and obvious omissions of accidentals.