About the Mazurkas

The mazurka is a stylized dance form combining the features of three Polish folk dances: the brisk mazur, the lively oberek and the slow kujawiak. The first mazurkas were written as early as the end of the 18th century and had a certain utilitarian function – they introduced folk music to the salons of those days. The most noted among the composers who wrote mazurkas were Karol Kurpiński, Mikołaj Kleofas Ogiński, Maria Szymanowska and Józef Elsner. Elsner had a considerable impact on shaping the artistic development of Fryderyk Chopin, being first his teacher in Warsaw and later a good friend.

In Chopin’s oeuvre, mazurkas evolved to independent lyrical pieces, meditative in nature. They were like a lens in which the composer’s deepest recollections of his homeland were focused in the form of images of Polish folklore captured on staff paper. Chopin composed mazurkas practically throughout his lifetime: he published 41 of them in 11 opuses, further two were published separately and a dozen or so remained in manuscripts. A striking feature about Chopin’s mazurkas is their form, clear yet astonishingly diverse, ranging from miniatures to elaborate musical poems (an outstanding example is the Mazurka in C major Op. 6 no. 5, with a special form, senza fine), as well as deliberate limitation of textural devices. The elements of folk stylization include numerous modalisms (particularly the Lydian fourth and the Phrygian second), ostinatos, bourdon fifths, sophisticated ornamentation (such as ornaments used in bel canto and transposed to instrumental ground). The key role is played by rubato, i.e. intentional unsteadiness of tempo resulting from prolonging or shortening certain notes by the performer.

Although in his mazurkas Chopin never made any direct quotes from folk music, its echoes permeate their musical substance. The essence of those dance miniatures was probably best captured by the Polish writer Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, who wrote: ‘In those fifty-odd short piano works the Polish composer contained the entire wealth of his soul, expressed his connection with the Polish people, offered the richness and refinement of his mind, and therefore we find in them such an abundance of musical ideas. Chopin’s mazurkas contain the recollections of all his voyages across Poland, memories of village songs and dances such as he came across in his wanderings on rural lanes’.

M.M.

The Mazurka in G major, Op. 50 No. 1

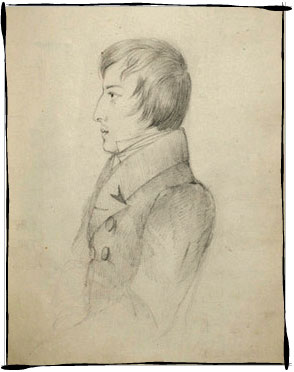

We do not know when Chopin began work on the new set of mazurkas that he completed and published in mid 1842 as opus 50, dedicated – in a spontaneous gesture of friendship – to Leon Szmitkowski, who took part in the November Uprising. Each of the three works brings music of a different tone, yet they are linked by a mazurka idiom that is no longer so directly dependent on music previously heard, on music brought from home.

The new mazurka idiom was characterised by a personal tone of hushed intimacy. There is a distinct trace – greater than the echo of rural music – of inner experiences. Chopin’s mazurkas become more expressive than reflective, and it is expression of an increasingly nostalgic tone. Even the shortest mazurka is now a little poem with its own dramatic structure, though the first of the three that comprise opus 50, in G major, brings the most numerous echoes and folk references of that kind.

Mazur-derived motives are followed by phrases of a kujawiak provenance, an elegiac dialogue of questions and answers. Then the light, colouring and expression suddenly change, before a climax and stretto in one – an attempted surge, in mazur rhythm and chromatic sonorities. But this mazurka does not end briskly or risoluto. It softens and fades, tinging the major with minor sonorities.

Author: Mieczysław Tomaszewski

A series of programmes entitled ‘Fryderyk Chopin's Complete Works’

Polish Radio 2