Concerti by Fryderyk Chopin

Chopin composed two piano concertos:

-

Concerto in F minor, Op. 21 (written 1829-1830, published 1836)

-

Concerto in E minor, Op. 11 (written 1830, published 1833)

It is worth noting that the opus numbers of these works do not correspond to the chronology of their composing but result simply from the order in which they were published. Hence the occasionally misleading designations of Concerto No. 1 in E minor and No. 2 in F minor.

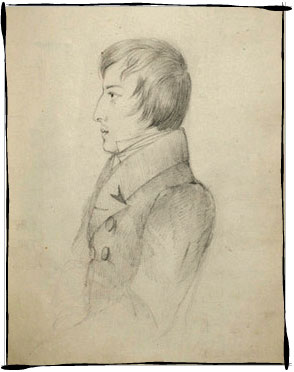

Chopin's concertos are generally considered to be the pinnacle achievements of the "Warsaw" period of his oeuvre (his childhood and youth until his departure from Poland in November 1830). The composer worked on them for about a year-from the autumn of 1829 to the autumn of 1830. He was aged nineteen-twenty at the time, and so these are works by a still very young composer, in which he achieved a remarkable maturity. Both concertos became widely renowned from the moment they were written, and still today they hold a firm place in the pianistic canon among the most celebrated Romantic concertos.

Chopin composed them in the style of the concert brillant, thus referring to a genre that was fashionable during his youth. Concertos of this type for piano and orchestra were written by the leading pianists of those times, including Hummel, Weber, Moscheles, Field, Kalkbrenner (to whom the E minor Concerto was dedicated), Ries and Dobrzyński. This genre was linked to the style brillant, which reigned supreme at that time among virtuoso pianists-a style characterised by great bravura, brilliance and technical display, as well as a fondness for tuneful, sentimental themes. The young Chopin adopted and developed many features of this style.

The two concertos are without doubt the most beautiful examples of the concert brillant convention. Despite the quite numerous discernible similarities to the style of Hummel, Field, Moscheles and Kalkbrenner, Chopin overshadows these composers through the depth and originality of his style. This personal, individual style of the young composer was fully manifest for the first time in the concertos, which-without ceasing to be brillant-are above all Romantic, poetic, youthfully ardent and fresh, written during the period of Fryderyk's first love for Konstancja Gładkowska.

They are three-movement works, adhering in general formal outline to the classical concerto model: the first movement is a sonata form, the second is a section in a slower tempo, and the third takes the form of a quick-moving rondo. It is the virtuosic and richly ornamented piano part that dominates, against the limited role of the orchestra.

The F minor Concerto is regarded as the more lyrical-even intimate and delicate. Particularly famous is its second movement (Larghetto) - "a temple of love and peace" (Iwaszkiewicz), seen as a musical confession of love. The Allegro vivace finale is a mazurka, including a stylisation of elements of the kujawiak and mazur.

The E minor Concerto - the later by around half a year-is a more amply proportioned work, written with great pianistic sparkle and panache. In its general conception it is similar to its predecessor. The first movement (Allegro maestoso), which exhales "an epic breath", makes use of three themes, the second movement (Romance) "is a sort of meditation on the beautiful springtime, but to moonlight" (Chopin's own words), and the Rondo finale this time constitutes a stylisation of another Polish national dance, namely the krakowiak, here treated with exceptional virtuosic bravura.

Chopin performed both his concertos in public shortly after their completion, at the Teatr Narodowy in Warsaw, in March and October 1830.

Artur Bielecki

(en.chopin.nifc.pl/chopin/genre/detail/id/5)

Piano Concerto in E minor, Op. 11

Barely had the applause died down following the presentation of the first of his two concertos, the F minor, in the early spring of 1830 at the National Theatre in Warsaw, than the twenty-year-old composer began sketching his next concerto, the E minor. By Easter, the Allegro maestoso (first movement) was already written. Chopin was more pleased with it than with the Allegro from the first concerto. In May, he completed the Larghetto, which he wrote in a particular mood. Mid-way through the month, he confessed to Tytus Woyciechowski: ‘Involuntarily, something has entered my head through my eyes and I like to caress it’. Biographers are in no doubt that Chopin was still under the spell of Konstancja Gładkowska, the ‘ideal’ to whom the Larghetto from the F minor Concerto had been ‘erected’. This young singer is present in some way in each of Fryderyk’s letters to Tytus: ‘Little is wanting in Gładkowska’s singing’, he reported following her appearance in Paër’s opera Agnese, ‘She is better on stage that in a hall. I shall say nothing of her excellent tragic acting, as nothing need be said, whilst as for her singing, were it not for the F sharp and G, sometimes too high, we should need nothing better’. In the Kurier Polski, however, Maurycy Mochnacki reviewed Gładkowska’s performance with rather different words: ‘Perhaps Miss Gładkowska did have a voice, but today, alas, she has it no more’.

In that same letter written to Tytus in May, the singer’s presence can be discerned in the words Chopin uses to describe the character of the middle movement of this work, which he had just composed: ‘The Adagio for the new concerto is in E major. It is not intended to be powerful, it is more romance-like, calm, melancholic, it should give the impression of a pleasant glance at a place where a thousand fond memories come to mind.’

The Concerto’s last movement, a Rondo, was written with some difficulty. It was a time of hesitation, procrastination and presentiment in Chopin’s life. Discussed throughout the summer of 1830 was the question of Chopin going out into the world, to test himself. ‘I’m still sitting here – I don’t have the strength to decide on the day […] I think that I’m leaving to die’. Before his departure, his new concerto was to have been completed, tried out and then presented to the Warsaw public. So in August, he finished the Rondo. In September, over three trial runs in private, he tested the sound of the whole work – first with a quartet and then with a small orchestra. He was able to declare, calmly, and not without some pride: ‘Rondo – impressive. Allegro – strong’. Finally, in October, he presented his new concerto to the public at large, at the National Theatre.

The E minor Concerto – rather unfortunately called the First on account of its being the earlier to be published – followed the path beaten by Chopin’s actual first concerto, the F minor, with which it shares both form and texture, and above all that poetical, youthful, romantic aura. The difference is that it seems to be written with a surer hand and a more experienced ear.

The character of the Allegro was clarified with the word ‘maestoso’, so frequent in the polonaises. It also conducts its narrative proudly and distinctly, with élan. It is suffused with the spirit of poetical animation, which in the times of Chopin’s youth was called ‘enthusiasm’. All three themes presented in the orchestral exposition climb or soar upwards, where they burst into song.

The first theme opens the work with a particularly vigorous gesture, taken up by the orchestral tutti. The principal theme, in the main key of E minor, is presented espressivo through the sound of the singing violins. The contrasting theme – even more tuneful, and brightened by a change of mood (from E minor to E major), was also entrusted by Chopin to the stream of sonorities in the strings. He did not forget about the wind instruments, but gave them a particular role: firstly, to transform themes already shown once; secondly, to accompany the piano with a discreet melodic counterpoint.

Yet before that can happen, the piano appears, backed only gently by the orchestra. The themes that the orchestra presented earlier are given a wonderful pianistic form. The opening theme is characterised by a spirit and flourish of which Beethoven might have been proud. In the principal theme, we hear the very distant, but distinct echo of a polonaise. The contrasting theme brings the aura of a nocturne.

First and foremost, Chopin’s concertos constitute a field of interplay between the themes, shown in their pure, flawlessly beautiful form, and the waves of sonorities of the pianistic figurations – breathtaking at times – that are derived from those themes.

The middle movement transports us into a world of acoustic magic. In the Larghetto – its character clarified in the score, following Mozart’s example, as a Romance – it is the spirit of reverie that holds sway. In a letter to Tytus Woyciechowski, the composer called it romance-like and melancholic, though he then added, to allay any doubts: ‘It is a kind of meditation on the beautiful springtime, but to moonlight’. He went on to explain to Tytus how that mood could be achieved: ‘by the playing of strings, the sound of which is muffled by sordini’, and so, as the composer rather humorously enlightens his friend, ‘a sort of comb, which spans the strings and imparts to them a new, silvery tone’.

We are transported into a world of soft, intimate music. The piano’s narrative drifts along at times on the edge of dream and reality, flowing like free improvisation, not subject to the dictates of specified form. The two themes (joined by the third) intertwine and modify one another. On its first appearance, the cantabile theme sounds against complete silence, simply and with reticent calm. It subsequently returns just the same, and yet not the same, decked with garlands of embellishments. The espressivo theme, reiterated after the strings, casts us into reflection and elation in turn. The mood of this daydream is suddenly interrupted. The third theme, agitato (in C sharp minor), brings a brief moment of perturbation and passion, before disappearing from view.

Then again we witness the magic of sonorities that are ever more subtle and thoughtful. The Rondo follows attacca, without a pause, rousing us from cogitation with the pungency of its dance rhythm, vivace tempo and powerful gestures. It draws us into dancing, amusement and play. The piano dallies with the orchestra, and the themes stand against the piano’s frenzied figurations.

The Rondo’s refrain bears the traits of a krakowiak: its rhythm, distinct articulation, liveliness and wit. The theme of the episode – led in octave unison against the pizzicato of the strings – brings yet more animation into play, despite beginning in a gentle dolce. The closing chase across the keyboard reminds one of the provenance of this supremely Romantic work: it was born of the virtuosic style brillant. Again the whole of Warsaw was drawn to the National Theatre for the premiere.

‘Yesterday’s concert was a success’, wrote Chopin on 12 October 1830 to Tytus Woyciechowski. ‘A full house!’ The Kurier Warszawski reported ‘an audience of around 700’. It was not just Chopin that was applauded, but also the two young female singers who agreed to accompany him in the concert and the conductor, Carlo Soliva.

Though it is hard to imagine such a thing today, the premiere of the E minor Concerto was broken up – as was the custom in those days – by an intermezzo. After the Allegro had been played through and ‘a thunderous ovation’ received, the pianist had to give way to the singer [‘dressed like an angel, in blue’] Anna Wołkow. Only after she had sung an aria by Soliva could the composer return to the piano to play the Larghetto and Rondo.

The other young singer was Konstancja Gładkowska. ‘Dressed becomingly in white, with roses in her hair [Chopin spared no detail in his description], she sang the cavatina from [Rossini’s] La donna del lago as she had never sung anything, except for the aria in [Paër’s] Agnese. You know that “Oh, quante lagrime per te versai”. She uttered “tutto desto” to the bottom B in such a way that Zieliński [an acquaintance] held that single B to be worth a thousand ducats’. That autumn concert, which took place seven weeks before the outbreak of a Polish national uprising, and three weeks before Chopin left Warsaw, was dubbed his ‘farewell’ concert. ‘The trunk for the journey is bought, scores corrected, handkerchiefs hemmed… Nothing left but to bid farewell, and most sadly’. In his trunk he carried an album into which Konstancja Gładkowska had written the words ‘while others may better appraise and reward you, they certainly can’t love you better than we’. Some two years later, Chopin would add: ‘they can’. That was in Paris, following his first public appearance at the Salle Pleyel. The E minor Concerto was enthusiastically received. François-Joseph Fétis, editor of the Revue musicale, wrote the next day: ‘There is spirit in these melodies, there is fantasy in these passages, and everywhere there is originality’.

Author: Mieczysław Tomaszewski

A series of programmes entitled ‘Fryderyk Chopin's Complete Works’

Polish Radio 2