Concerti by Fryderyk Chopin

Chopin composed two piano concertos:

-

Concerto in F minor, Op. 21 (written 1829-1830, published 1836)

-

Concerto in E minor, Op. 11 (written 1830, published 1833)

It is worth noting that the opus numbers of these works do not correspond to the chronology of their composing but result simply from the order in which they were published. Hence the occasionally misleading designations of Concerto No. 1 in E minor and No. 2 in F minor.

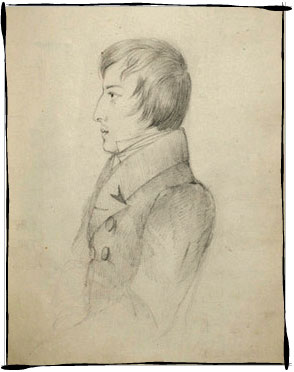

Chopin's concertos are generally considered to be the pinnacle achievements of the "Warsaw" period of his oeuvre (his childhood and youth until his departure from Poland in November 1830). The composer worked on them for about a year-from the autumn of 1829 to the autumn of 1830. He was aged nineteen-twenty at the time, and so these are works by a still very young composer, in which he achieved a remarkable maturity. Both concertos became widely renowned from the moment they were written, and still today they hold a firm place in the pianistic canon among the most celebrated Romantic concertos.

Chopin composed them in the style of the concert brillant, thus referring to a genre that was fashionable during his youth. Concertos of this type for piano and orchestra were written by the leading pianists of those times, including Hummel, Weber, Moscheles, Field, Kalkbrenner (to whom the E minor Concerto was dedicated), Ries and Dobrzyński. This genre was linked to the style brillant, which reigned supreme at that time among virtuoso pianists-a style characterised by great bravura, brilliance and technical display, as well as a fondness for tuneful, sentimental themes. The young Chopin adopted and developed many features of this style.

The two concertos are without doubt the most beautiful examples of the concert brillant convention. Despite the quite numerous discernible similarities to the style of Hummel, Field, Moscheles and Kalkbrenner, Chopin overshadows these composers through the depth and originality of his style. This personal, individual style of the young composer was fully manifest for the first time in the concertos, which-without ceasing to be brillant-are above all Romantic, poetic, youthfully ardent and fresh, written during the period of Fryderyk's first love for Konstancja Gładkowska.

They are three-movement works, adhering in general formal outline to the classical concerto model: the first movement is a sonata form, the second is a section in a slower tempo, and the third takes the form of a quick-moving rondo. It is the virtuosic and richly ornamented piano part that dominates, against the limited role of the orchestra.

The F minor Concerto is regarded as the more lyrical-even intimate and delicate. Particularly famous is its second movement (Larghetto) - "a temple of love and peace" (Iwaszkiewicz), seen as a musical confession of love. The Allegro vivace finale is a mazurka, including a stylisation of elements of the kujawiak and mazur.

The E minor Concerto - the later by around half a year-is a more amply proportioned work, written with great pianistic sparkle and panache. In its general conception it is similar to its predecessor. The first movement (Allegro maestoso), which exhales "an epic breath", makes use of three themes, the second movement (Romance) "is a sort of meditation on the beautiful springtime, but to moonlight" (Chopin's own words), and the Rondo finale this time constitutes a stylisation of another Polish national dance, namely the krakowiak, here treated with exceptional virtuosic bravura.

Chopin performed both his concertos in public shortly after their completion, at the Teatr Narodowy in Warsaw, in March and October 1830.

Artur Bielecki

(en.chopin.nifc.pl/chopin/genre/detail/id/5)

Piano concerto in F minor, Op. 21

As I already have, perhaps unfortunately, my ideal, whom I faithfully serve, without having spoken to her for half a year already, of whom I dream, in remembrance of whom was created the adagio of my concerto’ (to Tytus Woyciechowski, 3 October 1829).

The Concerto in F minor, the first of Chopin’s two concertos (though published as the second), was written between the early autumn of 1829 and the early spring of the following year. It was composed in accordance with the requirements of the genre, in line with the model derived from Mozart, but adopted directly from Hummel, whose influence is clearly discernible. There is no doubt that the pianistic texture of this work was shaped by the technique termed style brillant. It should be added, however, that in both Chopin’s concertos (written on a single wave of inspiration), the ‘brilliant’-style virtuosity was taken to its pinnacle. It was also overcome, by restoring to the themes a Classical, Mozartian simplicity (in the style brillant, they were often somewhat pretentious or banal) and by infusing the whole work with typically Romantic expression, no longer sentimental, but perceived as poetical.

When listening to works that could have served as exemplars for Chopin, such as concertos by Hummel, Moscheles, Ries and Kalkbrenner, we gain quite a peculiar impression. Every so often, we come across phrases, passages or sections that are ostensibly identical to those in Chopin. But only ostensibly, as they are lacking distinctness, colour and personal, individual expression. They are pale, conventional, external and superficial. All those composers, whose works we most often encounter solely in ‘historical’ concerts, speak the same language as Chopin, with the same set of idioms of pitch motion and rhythm. Yet he not only speaks, he has something essential and highly original to say to us. ‘I say to the piano what I would have said to you many a time’, he related to Tytus Woyciechowski. The music of his concertos expresses his personality. From beyond the conventions and the language of the epoch, Chopin’s face peers out, and at the same time a genre of Classical structure and ‘brilliant’ texture is transformed into a Romantic genre. The typical structure of the cycle, comprising Allegro – Adagio – Presto, turns into the structure Maestoso – Larghetto – Vivace, in which Maestoso means a lively or a pondering march, the Larghetto is a nocturne, and the Vivace is a dance – a stylised kujawiak.

The first movement of this triptych, marked with a maestoso character, suffused with expression that oscillates between Classical loftiness and Romantic enthusiasm, proceeds according to the principles of the sonata allegro. The exposition presents the themes, the development transforms them beyond recognition, and in the reprise they meet once again, although altered somewhat. Also in keeping with a convention established in concerto allegros, the themes are shown first in the orchestra, and only then in the piano. The opening theme, which is also the main one (in F minor), proceeds in the rhythm of a mazur that is now songful, now solemn. Its head motif, in a dotted rhythm, becomes a ubiquitous motto throughout the whole allegro.

In the orchestra, the initial theme of the Allegro appears modestly and almost imperceptibly. In the piano, however, it is impressively announced. It resounds in silence, against the background of the orchestra, which is suddenly hushed.

Immediately after the initial theme, Chopin has the pure, songful complementary theme sound for just a brief moment, bringing to mind the melodies of Mozart’s concertos. This theme develops into a swinging cantilena, before fading away.

The theme set against the opening theme, in a different mode and key, proceeds in A flat major. It is of a romance-nocturne character, thereby presaging the concerto’s middle movement, Larghetto. In the orchestra, were it not for the piercing tone of the oboe, it would pass all but unnoticed, as it only really blooms in the piano. This theme also resounds in silence, like a nocturne.

The exposition is followed by the development. Its opening introduces a mood of meditation or reflection. But just a moment later a frenzy of figuration is unleashed. An unchecked stream of piano sonorities flows through nearer and more distant keys. In the orchestra, we hear fragmented motives from the themes presented earlier.

The development ends with an explosion of sonorities in the full orchestra. Then, after a quieting and relieving of the tension, the reprise appears, and so the return of the themes that were presented at the beginning. This time, they are all spliced together. The contrasting theme stands opposite the initial theme just a moment after its reappearance. There then ensues a moment of mysterious concentration.

The second movement of the Concerto, the famous Larghetto, is its central part. One might say that the whole work owes its raison d’être to this movement. The opening bars in the orchestra already lead us into a different time and a different dimension: half-real, half-oneiric. Of the piano’s entrance, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz said that it ‘sounds like the opening of a gate to some haven of love and peace’.

The Larghetto has the character of a nocturne and the form of a grand da capo aria. Its principal theme appears twice more. On each occasion, Chopin has it played molto con delicatezza, yet each time he arrays it in new, increasingly airy ornaments. The third time, the phrase originally comprising eight notes gains the form of a wave, expressed by a forty-note fioritura. An inimitably Chopinian mood is forged.

That dreamy atmosphere forms the framework of the Larghetto. It is filled by music that is thoroughly different, although still adhering to the same, supremely Romantic poetic. Agitated, violent sonorities burst in. Chopin has them played con forza and appassionato, as if some hitherto suppressed plenitude of emotion was being revealed at that moment.

Among those to use a piano recitative against the background of an orchestral tremolando in a similar way were Ignaz Moscheles, in his Concerto in G minor, and Ignacy J. Dobrzyński, in his Concerto in A flat major, though the way they did it cannot compare with Chopin.

The third movement of the F minor Concerto, the movement that closes the work, is a Rondo, as the genre’s convention dictates. It thrills us with the exuberance of a dance of kujawiak provenance. It plays with two kinds of dance gesture. The first, defined by the composer as semplice ma graziosamente, characterises the principal theme of the Rondo, namely the refrain.

A different kind of dance character – swashbuckling and truculent – is presented by the episodes, which are scored in a particularly interesting way. The first episode is bursting with energy. The second, played scherzando and rubato, brings a rustic aura. It is a cliché of merry-making in a country inn, or perhaps in front of a manor house, at a harvest festival, when the young Chopin danced till he dropped with the whole of the village. The striking of the strings with the stick of the bow, the pizzicato and the open fifths of the basses appear to show that Chopin preserved the atmosphere of those days in his memory.

The opening key of the Rondo finale is F minor, a key with a slightly sentimental tinge. According to Marceli Szulc, it brings ‘wistful reflection’. But the Concerto ends by shaking itself out of reflection, nostalgia and reverie, with the appearance of a horn signal denoting the start of the dazzling coda and the entrance of the simple, cheerful key of F major.

On the grand stage of the National Theatre, the F minor Concerto was heard in Chopin’s first truly grand concert, on 17 March 1830. That premiere was preceded by two semi-private rehearsals: the first in February, among family and close friends; the second at the beginning of March, also in the Chopins’ drawing-room, in the presence of the musical elite of Warsaw: Elsner, Kurpiński and Żywny. On that occasion, the orchestra part was played by chamber forces.

The Concerto in F minor became a point of departure for the Romantic concerto, together with the Concertos in A minor by Schumann and in G minor by Mendelssohn. Zdzisław Jachimecki noted that its unique poetry may have been determined by ‘its certified provenance from personal experience’. There is no denying it: the F minor Concerto does indeed come across as a work of youthful inspiration, set in flight by the emotions of a first love.

This work was inspired by Chopin’s feelings for Konstancja Gładkowska, but it was published a few years later with a dedication to Delfina Potocka.

Author: Mieczysław Tomaszewski

Cykl audycji "Fryderyka Chopina Dzieła Wszystkie"

Polish Radio, program II

(en.chopin.nifc.pl/chopin/composition/detail/page/2/id/66)