The Ballade Genre

In the times of Chopin, the ballade had three equally popular connotations. The term “ballade” mainly referred to the literary form – combining characteristics of epic (narrative, plot), poetry (emotionality) and drama (dialogues and action), on themes drawn from stories and folk tales, plenty of fantastic events, magic and frequent interventions of supernatural powers. The genre, universalised by such authors as Gottfried August Bürger (Lenore), Johann Wolfgang Goethe (The Erlking), Friedrich Schiller (The Glove), Heinrich Heine (Lorelei) or Adam Mickiewicz (Świteź, Świtezianka), enjoyed great popularity in the era of Romanticism.

A natural consequence of the literary ballade’s popularity was to transfer it to the musical ground. Therefore, on the one hand, one created vocal ballades for solo voice or accompanied by an instrument, being a musical illustration of works by contemporary poets. The literary creation proved to be a remarkably graceful object to be set into music – fast-paced action, dialogues between the characters, supernatural phenomena, nature coming alive and eventually magic, fantastical personages – all these elements allowed to apply a number of unobvious musical resources and solutions: Harmonic, rhythmic, dynamic or agogic, which created an atmosphere corresponding to the ballade’s content and illustrated the events which were happening therein and the accompanying them emotions. Franz Schubert is an example of a composer who used the potential of literary ballades to the fullest; he composed music to, among others, collections of poetry by Schiller (e.g., Der Taucher), Goethe (e.g., Erlkonig) or Heine (songs from the cycle Schwanengesang). On the other hand, ballades started to appear in operas, as an element describing events taking place beyond the stage, often becoming an opportunity for composers to show their skills, hence also for a vocalist’s abilities. One of the most popular pieces of this kind was, among others, Raimbaut’s ballade from Giacomo Meyerbeer’s opera Robert the Devil (1831), as well as Senta’s ballade from Richard Wagner’s opera The Flying Dutchman.

The ballade as a strictly instrumental genre was not born until under Chopin’s fingers. The first sketches of the Ballade in G minor, Op. 23 were created already in the middle of the 1830s, three subsequent appeared in print in 1840-1843. The time during which Chopin worked on the ballades belonged to the most creative in his compositional career, as it was in 1835-1843 that such masterpieces as the Fantasy in F minor or four Scherzos were created, which, to a certain extent, are related to the ballades due to, among others, their free, yet at the same time extensive form. The form of the ballades is not based on schemes but on basic formal rules such as synthesis, antithesis, sequence, development, transformation, variation or reprise. The main driving force of the ballades is the theme and its transformations, while the means used to achieve this aim are mainly melodic, dynamic, agogic or rhythmic contrasts.

According to Robert Schumann’s memories, Chopin “would then say that he was incited to his ballades by a few poems by Mickiewicz.” Despite numerous attempts to find direct references to Świtezianka or Lorelei in Chopin’s ballades, the researchers have not been able to prove the existence of such a dependence. However, lack of a clear programme or illustrative character does not mean that it is pointless to look for a story in Chopin’s ballades. The content, unexpressed with words, is hidden in plenty of expression themes, while the narrative tone guides the hearer through the meanders of waving melodies or impulsive passages. Numerous contrasts introduce plot twists, while the unobvious harmonic solutions leave an impression of an understatement, obliging the hearer to interpret the open ending on his own.

Although it could seem that four pieces are not yet a genre, Chopin achieved a new quality in the ballades, different from the one in the genres he had written before. In spite of the clear genre affiliation, each of the ballades has its own unique character of an enormous emotional load. The gloomy Ballade in G minor, Op. 23 develops the form of sonata allegro in a particular way; in the Ballade in F major, Op. 38, the main driving force are contrasts; the Ballade in A-flat major enchants the hearer with its radiantly idyllic themes, while in the Ballade in F minor the lyrical element unfolds variationally, falling into a net of dense polyphony. This diversity of moods, even within one piece, narrative character and extensive form induced the researchers to determine the instrumental ballade as a “piano poem.”

It is hard to say whether the further fate of piano ballade is a consequence of Chopin’s pieces or whether it developed independently on the ground of vocal ballade. Although the works of this genre composed later by Johannes Brahms, Franz Liszt, Edward Grieg or Gabriel Fauré did not reach the level of Chopin’s ballades, they enjoyed a great popularity among the contemporary audience. The ballades by César Franck (Op. 9) and Liszt (the Ballade in D-flat major), similarly as Chopin’s ballades, did not refer to any literary original. However, a ballad from Op. 10 by Brahms already indicates a direct association with the Scottish ballade Edward from Johann Gottfried Herder’s collection The Voices of the People. The piano ballade also influenced the development of orchestral music, anticipating the creation of the symphonic poem genre.

Ballade in F major, Op. 38

In the original meaning, the ballade referred to the dance form of interlude in the Italian stage music (Italian: ballare – to dance). In the 19th century, it lost that meaning in favour of the forms described above, however the echo of its dance origins is clearly audible in Chopin’s ballades, particularly in the Ballade in F major, Op. 38. The piece opens with a slow theme, maintained in the rhythm of the Italian siciliana, which begins to tell its story, as if it were the narrator, with dancelike movements. The theme’s melodic line oscillates around the tonal centre, not moving too far from it, neither melodically nor harmonically. The initial narration is suspended by an extended Chopin chord only to make room for a new narrator – the impulsive presto con fuoco of a dramatic, plenty of emotions tenor. From this moment on, these two opposing characters will clash in battle for the hearer’s attention, leading to an unobvious, sudden finale – as the seemingly victorious first theme is not shown in the initial key, F major, yet in the parallel A minor, thus obliging the hearer to interpret the ending on his own.

The omnipresent extreme contrasts are the driving force of the Ballade – the first theme, slow, unusually calm, even idyllic, gives place to an agitated one, plenty of dynamic passages and dense chromatics. The contrasts are to be observed in almost every element of the piece: The cantilena of the first theme is juxtaposed with the figurations in the second theme; the slow, monotonous rhythm of siciliana contrasts with the furious race of the second theme, plenty of sudden turns and changes; the first theme concentrates around the middle register, while the second theme uses the piano’s registers to their fullest extent. Such strongly opposed themes compete with each other, at the same time influencing themselves. Such a shape of the piece’s form was undoubtedly influenced by the composer’s stay in Majorca – cold, intimidating walls of the monastery in Valldemossa, first symptoms of the disease and very bad mood had to left their mark on the emotions included in the Ballade.

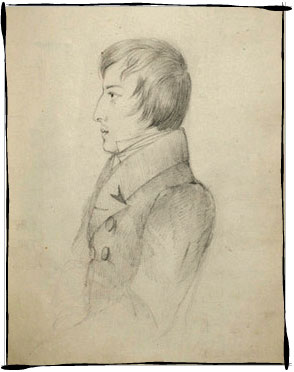

Although the Ballade in F major left a puzzle in the form of the “tonal duality” of the piece, it helped to solve another: Thanks to the preserved manuscript sources of the Ballade, it has been possible to identify Adolphe Gutmann as the second (after Julian Fontana) main copyist of Chopin’s works. Among all editorial copies, whose authorship can now be assigned to Gutmann, only in the case of the Ballade it was possible to compare the copy with the preserved autograph. The fact of finding Gutmann’s letters and his musical manuscript – an eight-bar entry to an album also contributed to the identification.

K.K.

On the basis of:

Mieczysław Tomaszewski

Cycle of broadcasts "Fryderyka Chopina Dzieła Wszystkie"

Polish Radio 2

Mieczysław Tomaszewski

Chopin. Człowiek, Dzieło, Rezonans

Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, Kraków 2010

Ewa Sławińska-Dahlig

Adolphe Gutmann – ulubiony uczeń Chopina

Narodowy Instytut Fryderyka Chopina, Warsaw 2013