The musical genre of Scherzo

Scherzo, from the Italian ‘joke’, is a musical term dating back to the 17th century, used to denote various types of musical works. Beginning from the times of Beethoven, the term scherzo predominantly related to a piece replacing the minuet in the sonata form. The term was also used to highlight the playful character of such pieces.

The first application of the term scherzo to a musical work can be found in the title of Gabriel Puliti’s publication Scherzi, capricci et fantasie, per cantar a due voci (1605) and in the collection of works by Claudio Monteverdi (Scherzi musicali, 1607). In that period, the term ‘scherzo’ served, along with such other terms as ‘madrigal’ and ‘canzonetta’, to describe a song with many stanzas written for voice with piano. Interestingly, the light-hearted connotation of the scherzo was not taken literally at all – apart from scherzi in secular music, there were also sets of religious musical works labelled with the same name. Very soon, scherzo became a purely instrumental piece; it can be found among the works of such composers as Johann Martin Rubert, Francesco Asioli or Georg Philipp Telemann.

In the early decades of the 18th century scherzi began to function as movements in larger musical forms. Initially, scherzi with the duple meter time signature and without a trio appeared as the final movement (e.g. Partita in A minor BWV 827 by J. S. Bach, or Invenzioni by Francesco Antonio Bonporti). Gradually, the scherzo came to replace the minuet, initially only as the description of the mood of a given piece (Haydn’s Quartets Op. 33 Gli scherzi), but later as a regular part of the sonata cycle.

However, it is to Ludwig van Beethoven that we owe the establishment of the scherzo as regular alternative for the minuet. In his early compositions scherzo already tended to occur regularly in that character, its name literally reflected in the musical matter. Beethoven’s scherzi epitomize his refined musical humour: they have fast tempos and clear pulse (Piano Trio Op. 1 no. 1), make use of the element of surprise (String Quartet Op. 18 no. 2) or an apparent contradiction of the co-performing instruments (Sonata for Violin and Piano Op. 24 ‘Spring’).

The thing that exerted the greatest influence on the output of later generations of composers was the introduction of the scherzo to the symphony. In Beethoven’s works the scherzo is always very energetic and vigorous due to a combination of fast tempo and rapidly changing texture. Beethoven also retains a traditionally contrasting trio, opposite in tempo or character.

The musical form of the scherzo acquired a new sense in the works of Felix Mendelssohn. This is particularly visible in the Scherzo from the Octet and in the music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Mendelssohn’s scherzi, usually with duple meter time signature, are very light, almost fairy-tale in character and their delicate pianissimo endings are manifestations of a certain mannerism.

At the end of the 19th century the scherzo was sometimes replaced with a dance-like movement of national (Dvorak’s furiant) or ballet (Tchaikovsky’s waltz) nature. Still, most composers still preferred to choose the scherzo as one of the movements for their symphonies, beginning from Anton Bruckner (the tempestuous, energetic scherzo with a prominent role of the rhythm, with a contrasting trio in landler style) and ending with Dmitri Shostakovich and his scherzo with elements of grotesque and caricature.

The earliest examples of the scherzo as an independent piece of music are three pieces by J. S. Bach (BWV 844, Anh 134 and 148) dating from his Köthen period and two scherzi written by Leopold Mozart. Such a type of scherzo flourished in the 19th century piano literature and brought some prominent works; the greatest examples are the four scherzi by Fryderyk Chopin, which are extended compositions with a three-part structure (except for the Scherzo in C sharp minor) and fast ¾ tempo. Usually, piano scherzi of that period were written as virtuoso displays of technical skills (works by Sigismond Thalberg, Edward Wolff or Stephen Heller) or characteristic works (piano miniatures), or a combination of both. Orchestral scherzos appeared in the 1st half of the 19th century (e.g. Clara Wieck’s piece dated 1831) and rose to greater prominence towards the end of the 19th century and in the 20th century thanks to the works of Dvorak or Paul Dukas (The Sorcerer’s Apprentice).

Scherzo in C sharp minor Op. 39

The last work inspired by Majorca and the atmosphere of Valldemossa was the Scherzo in C sharp minor. It was there that the Scherzo was certainly sketched (in January 1839, Chopin offered it to Pleyel for publication), though it was not completed until the spring, in Marseilles. Work on the manuscript was interrupted by a strong recurrence of his illness. From the very first bars, questions or cries are hurled into an empty, hollow space – presto con fuoco. And hot on their heels come the pungent, robust motives of the principal theme of the Scherzo, played fortissimo and risoluto in double octaves (bars 25–56).

The music is given over to a wild frenzy, mysteriously becalmed, then erupting a moment later with a return of the aggressive octaves. And then… the tempo slows, the music softens. Like a voice from another realm comes the focused, austere music of a chorale, interspersed with airy passages of beguiling sonorities (bars 152–191).

The chorale returns many times over, and with it those airy garlands of sound. The octaves theme also returns. And this appears to be a reprise announcing an imminent finale. But Chopin did not cast his Scherzo from that simplest of moulds. Again the chorale-filled trio returns. As its song is reprised, it slips from the hard E major into the gentle, but sad and mysterious (uttered sotto voce), E minor (bars 494–514). This altered theme concludes with question marks, imbued with mystery and expectation, soaring upwards in the utmost silence (bars 526–539). And we have the most beautiful moment in the whole of the Scherzo: the apotheosis of the chorale. Through a sequence of chords that progress calmly upwards (now in C sharp major), the music attains ecstasy (bars 542–567).

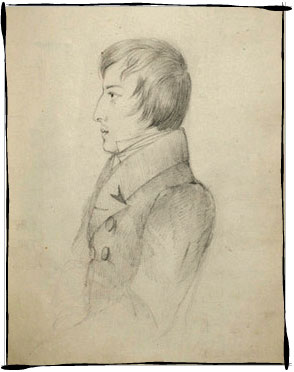

The finale is played out in two parts. The run to the finish is commenced by passages that surge up the keyboard, before the whole work ends with a series of chords that bring a distinct gesture of closure in a victorious key, transformed from C sharp minor to C sharp major (bars 628–649). Published as opus 39, the Scherzo in C sharp minor was dedicated to Adolf Gutmann and probably composed with him as performer in mind, as it offered Gutmann plenty of opportunity to show off his technical skills, ability to operate with contrasts or the power of his sound that was often exaggerated and ridiculed by other Chopin’s students jealous of Gutmann’s position as the master’s favourite pupil. Chopin was very pleased with Gutmann’s interpretation, so he entrusted to him the first performance of the Scherzo in the company of friends, including Ignaz Moscheles, who highly praised that performance. Gutmann was also the author of the Stichvorlage copy of the Scherzo, as well as some other Chopin’s works, thus becoming – apart from Fontana –of the two main copyists of Chopin’s works.

Katarzyna Koziej

Based on:

Author: Mieczysław Tomaszewski

The cycle ‘Fryderyk Chopin’s Complete Works’

broadcast by Polish Radio Channel Two

and

Author: Ewa Sławińska-Dahlig

‘Adolphe Gutmann – Chopin’s Favourite Pupil’

The National Institute of Fryderyk Chopin, Warsaw 2013